Ever since August 2022, when Texas Governor Greg Abbott initiated the transportation of migrants to Chicago, the presence of asylum-seekers has had a profound impact on the city and its surroundings.

More than 47,200 people, largely from Venezuela, have traveled through Chicagoland, and tens of thousands have settled here. Local officials have opened over 20 buildings to temporarily shelter them, costing hundreds of millions of dollars. They’ve seen record crowds at hospitals, schools, and food pantries.

Abbott did not create the migrant issue over the last two years, but he exacerbated it, pushing Democrats to reconsider their party’s stance on accepting immigration commitments.

Today, according to a June executive order signed by President Joe Biden, buses are no longer arriving in Chicago at the same rate as in 2023. The situation, which officials have long dealt with, is entering a new phase. Migrants have experienced four seasons in the city. They’re moving into neighborhoods. Some are even traveling to the city on their own after hearing it’s a fantastic place to live.

“Our job is creating long-term community connections for these families,” said Matt DeMatteo, executive director and pastor of New Life Centers, a nonprofit group that assists migrants in conjunction with the city and state. “A beautiful tapestry of spaces and places.”

Indeed, while some migrants have found stability via employment and community, many others are still struggling to survive as they live in difficult circumstances and struggle to find work and attend school.

The Tribune interviewed hundreds of migrants over the last two years and followed up with five to discover how their lives have unfolded in the City of Big Shoulders.

Marilieser Gil-Blanco

Marilieser Gil-Blanco credits his continued existence to his decision to migrate to the United States.

Last summer, while traveling from Venezuela with his pregnant wife and daughter, the 24-year-old man experienced paralysis from the chest down. This was caused by a rare condition known as transverse myelitis, which is characterized by inflammation of the spinal cord. Like many other migrants, he has heavily relied on volunteers and medical resources in Chicago since his arrival.

Caring for him has been a challenging task for his partner, Genesis Chacón, who has taken on the responsibility of looking after their newborn and 4-year-old child while also tending to his needs, such as changing his diapers and repositioning him in bed.

After the Tribune reported their story in February, the family received more than $80,000 through a GoFundMe page that volunteers had set up. However, managing the money among family members proved to be a challenge. Then, in March, tensions escalated when Gil-Blanco discovered that Chacón, 23, was dating someone else.

“We began arguing, and things got really intense, even in front of our daughters,” he said.

Emily Wheeler, program manager for the Faith Community Initiative, who has been assisting the family, expressed that looking after Gil-Blanco and the children proved to be challenging for Chacón.

“In April, she contacted us and expressed her decision to no longer live with him. She said that she was taking the girls with her and leaving,” Wheeler revealed.

After receiving her share of the money, Chacón decided to relocate to a hotel room. However, she later returned home upon Gil-Blanco’s suggestion, believing it would be more beneficial for their daughters to have her present. Subsequently, in July, they found a new apartment and moved there.

Gil-Blanco is unable to muster the courage to set up an appointment for therapy sessions at Cook County Hospital. This hospital has provided healthcare services to an astounding number of 34,800 migrants, including Gil-Blanco, through a total of 121,000 visits to its health centers and hospitals.

Gil-Blanco frequently finds himself succumbing to a profound sense of sadness. He often dreams of being able to walk again, yearning for the ability to perform various tasks that are currently beyond his reach.

On a typical weekday, he sat on a cozy mattress in his newly acquired house in the Grand Crossing neighborhood. As he observed his eldest daughter Mila gleefully darting around him, her curls bounced playfully.

“I’ve experienced moments of solitude,” he shared, “but my daughters are my source of resilience. Witnessing their growth right here is what keeps me going.”

Betzabeth Bracho

Betzabeth Bracho, 34, spent seven months sleeping on an air mattress at the Calumet District (5th) police station before finding shelter in a migrant shelter and eventually moving into an apartment with her husband, Carlos Ramírez, who used to be a police officer in Venezuela.

In June, Bracho and Ramírez left Venezuela due to their opposition to the government led by Nicolás Maduro, the far-left president. Bracho mentioned that the police officers at the station were unaware that her husband had also served as an officer in his home country.

When the Tribune first encountered the couple in June of last year, they were in a dire situation. They relied on donated food and had to use a bucket for showering in the police station bathroom. However, they have made significant progress since then. Bracho has found employment at a nail salon, and they now reside in an apartment with other migrants. Despite these improvements, Bracho still longs for her life back in Venezuela, where she was pursuing her dream of becoming a preschool teacher.

“We didn’t choose to be here,” she expressed.

Bracho and Ramírez made the difficult decision to leave their two sons, aged 9 and 12, in Venezuela with their family. Despite being separated, Bracho makes it a point to call them every day to stay connected.

Bracho expressed her concern for her children’s safety following Maduro’s claim of victory in the July election, which sparked widespread protests throughout Venezuela. She discussed the possibility of relocating them to Colombia or even to her current location. In early August, Bracho participated in a demonstration in the Loop, protesting what is considered one of the country’s darkest periods in its decade-long decline. She proudly wore a shirt adorned with the words “Free Venezuela” painted in the colors of the national flag.

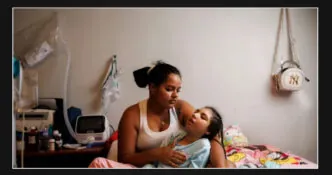

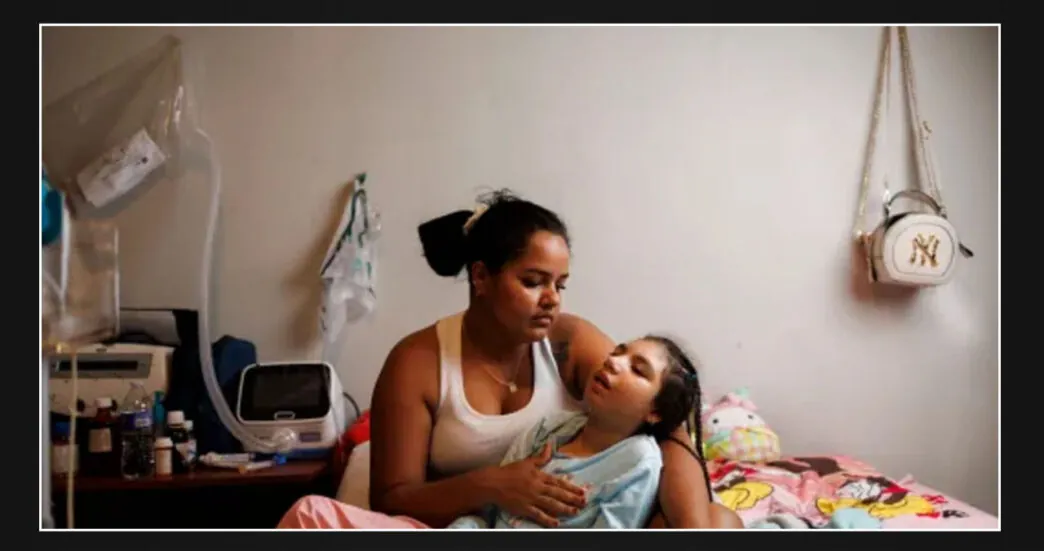

Yamile Pérez

Last November, 28-year-old Yamile Pérez embarked on a journey to secure a brighter future for her 8-year-old daughter, Keinymar Ávila. Keinymar, a petite child with microcephaly, faces numerous challenges such as seizures, developmental delays, and intellectual disability. Determined to provide her daughter with access to education, Pérez made the arduous journey, spanning thousands of miles, in search of better opportunities.

However, Keinymar did not attend. Instead, on the opening day of classes this year, she remained at home, fighting a high fever of 104 degrees and dealing with bedbug bites on her arms and legs.

Pérez attributes her daughter’s deteriorating health to the dilapidated apartment in the South Shore neighborhood where they currently reside.

According to the Keinymar family, they have made multiple attempts to clean and disinfect their apartment. However, due to financial constraints, they are unable to discard their infested clothes and furniture. During a visit to their apartment in early August, bedbugs were observed crawling on their mattress.

Both Pérez and her husband do not possess legal work permits. A collaborative effort between the federal, state, and local governments, along with the shelter system, has organized a workshop to assist over 8,700 migrants in submitting permit applications. Unfortunately, Pérez was unaware of this opportunity, and due to the sporadic jobs she has managed to secure, she cannot afford to relocate to a different apartment.

“I simply desire to be in a location where my daughter can feel safe and secure,” she expressed with heartfelt concern.

According to her, there are several other migrant families residing in the building. She mentioned that when these families take showers, the water from the pipes upstairs ends up running down the walls in her bathroom. The situation is so severe that even doctors refuse to do home visits.

Pérez expressed frustration with the landlord, stating, “I have repeatedly informed them about my child with special needs. They are aware that repairs are necessary for the house.”

Lori Wyatt, one of the property managers, explained that exterminators have made multiple attempts to treat Pérez’s apartment. As part of the process, they have advised her to bag or dispose of her bedding. According to Wyatt, once an infestation like this occurs, it becomes extremely challenging to eradicate.

Pérez mentioned that she would go back to Venezuela or relocate to another state if it wasn’t for Keinymar’s condition and the strong support system she has established here. During the day, Pérez and her husband work in painting and cleaning jobs, and she often depends on the assistance of her friends to manage things at home.

She said that her little girl is always at risk of having a seizure.

Living in the same apartment building, the biggest source of solace for her has been the community of fellow migrants. The children in particular have provided a much-needed respite for her 9-year-old son, Keinar, who enjoys spending time with them in the backyard.

A victim of abuse

A Venezuelan woman, whose identity is being protected due to her status as a victim, recently experienced a traumatic incident while searching for an apartment in the Roseland neighborhood. Two months after being sexually abused, she found herself targeted once again, this time falling victim to an attack and robbery near her residence. During the incident, her immigration documents and valuable possessions were stolen.

Fear has consumed her due to two consecutive incidents. As her husband goes to work, she finds herself confined to their home in the Austin neighborhood, constantly on edge. Inside the apartment, her sons play, pretending to rev engines on their invisible motorcycles.

At the start of summer, a woman was excited to venture out from the shelter she had been residing in. She came across an apartment listing on Facebook for a room in the Roseland neighborhood.

In July, the woman shared her harrowing experience with the Tribune, recalling how she instinctively reached out to protect her son when the incident occurred. She vividly remembers how her son clung onto her tightly, refusing to let go.

A couple of weeks ago, during a birthday party at a friend’s house, the woman experienced her second attack. She had gone to a corner store across the street to purchase some additional food when a man approached her and demanded her wallet. Frightened, she began to scream, believing it was the same attacker from before.

Despite filing a police report in early August, the woman has yet to receive any updates or information from the detectives assigned to her case. Frustrated and filled with emotion, she tearfully questioned, “What more do I have to endure for the detectives to take action? Must I be raped and killed?”

Angélica Beltrán

On Monday, Angélica Beltrán, 45, and her son, Engerberth Morales, posed for a photo in front of the Bean. Just a week prior, she had thrown a grand celebration for his ninth birthday. The party was filled with joy as they gathered with over 20 kids, all of whom they had met since their arrival in Chicago last July. The cake adorned with white and green frosting was a highlight of the festivities.

When the Tribune initially met Beltrán and her son, Engerberth, earlier this year, the situation was completely different. Engerberth was in tears as he made his way to school. At that time, the family was enrolled in a state housing program that allocated $53 million to assist migrants in obtaining housing. This program facilitated the relocation of migrants into more than 6,000 homes, as confirmed by a state spokeswoman’s data.

Beltrán was grateful to the state for assisting her with six months of rental payments. However, in their haste to leave the migrant shelter, they ended up moving to a cramped apartment in Englewood. Additionally, the surrounding neighborhood gave them an uneasy feeling of insecurity.

The family has recently relocated to a different apartment in Englewood, seeking more space and a quieter neighborhood.

Beltrán and her husband, who are from Venezuela, obtained work permits a few months ago by applying for temporary protected legal status. This special status enables individuals from specific countries to reside and be employed in the United States.

The couple has secured employment at restaurants on the South Side. They can now cover their rental payments and are also saving up for a car.

Enrolling Engerberth in school is currently Beltrán’s main concern. He is unable to read, which has led to him discontinuing his education last year due to the embarrassment of not being able to speak English. Beltrán had hoped to enroll him in a bilingual school, but unfortunately, there wasn’t one in close proximity.

“I find it challenging to communicate with others,” he expressed.

Chicago Public Schools reports that as of April 12 this year, they have served approximately 9,800 new arrival students. In an effort to support these students, the number of teachers certified in bilingual education, English as a Second Language, or both has increased by nearly 40% since 2018. However, many of these students find themselves in schools where there are very few classmates who speak Spanish. Despite the challenges, Beltrán was determined to give her son, Engerberth, another chance at attending school this year after understanding the difficulties he faced during their transition to a new country.

Yoel Guerra

On a warm summer night in the Little Village neighborhood, Yoel Guerra and his teammates gathered on a baseball diamond. They formed a circle, holding hands and offering a prayer. Yoel, a 16-year-old from Venezuela, expressed his fondness for Little Village Summer Softball, highlighting its unique nature compared to school baseball or his Cubs traveling team. He particularly enjoys playing on Thursday nights during the summer, as it allows him to interact with people of different ages, including his stepdad.

Guerra’s family, consisting of seven members, resides close by, and his younger siblings cheer from the sidelines during their games. They enjoy snacking on Cheetos and playing around in the nearby fields. As for Guerra, who has been involved in baseball since the tender age of 4, the game serves as both a sanctuary and a nostalgic reminder of home. It offers him a chance to relax and concentrate on a single activity.

Guerra’s passion for baseball goes beyond mere enjoyment; he possesses natural talent in the sport. With his coaches recognizing his potential, there is a possibility for him to play in college. Understanding the significance of academics, he is dedicating himself to improving his grades this year.

Furthermore, Guerra is fully committed to the team goals of Farragut Career Academy. Following their victory in the conference last year, they have advanced to higher divisions and aim to secure another triumph. Appreciating the sense of community within the academy, Guerra expressed his love for it.

Baseball, being the most popular sport in his home country, provides Guerra with a daily source of anticipation and inspiration as he finds role models within the United States.